JILPT Research Report No.183

Research on Employment at NPOs:

Assessing Change Caused by Continuous Growth and Disasters

May 31, 2016

Summary

Research Objective

The purpose of this research is to conduct empirical analysis on the employment at NPOs (nonprofit organizations) based on a survey. The survey dealt with Specified Nonprofit Activity Corporations (referred to below as Nonprofit corporations), which are probably perceived as the most typical examples of “NPOs” in Japan. JILPT conducted a similar survey targeting Nonprofit corporations 10 years ago, and this research aims to ascertain what changes have occurred over those 10 years. This time, questions on support activity were added to discover facts aimed at analyzing the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on NPO activity.

Research Method

Analysis of survey research

Main Findings

- Potential for employment creation at NPOs

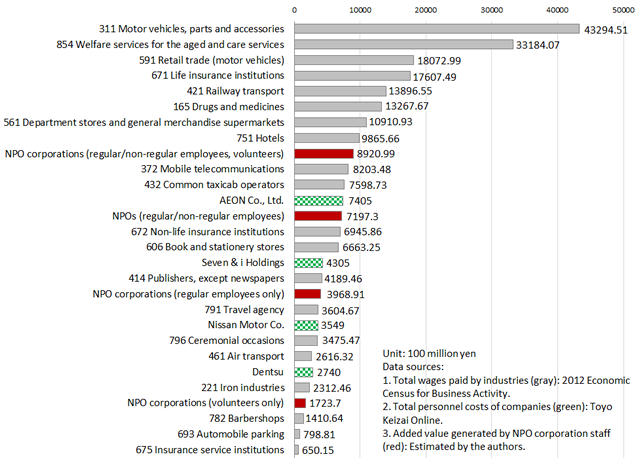

In Chapter 2, we attempt to estimate the scale of the labor market for Nonprofit corporations and assess the relative size of the market in comparison to industrial sectors. As a result, the added value generated per year by volunteers and paid staff of Nonprofit corporations was estimated to be a total of 892.1 billion yen. Comparing this to other industrial sectors, it is larger in scale than “Mobile telecommunications (mobile telephone business, etc.)” and “Non-life insurance institutions” (Figure 1). The number of employees per organization is expected to expand in future, along with an expansion in the number of organizations. For this to occur, however, it will be necessary to improve the management structure, which still remains small in scale.

Figure 1. Added value generated by paid and unpaid staff of Nonprofit corporations compared to industries and companies

In Chapter 3, in view of factors behind the increase in paid staff per Nonprofit corporations, we identify determinants of the number of paid staff from organizational survey results. As a result, the increase in paid staff over the last 10 years is observed mainly in regions with smaller populations. Regular staff, in particular, tend to be more common in areas where the market wage is low. On the other hand, non-regular staff are more common in areas where the market wage is high. Although wage levels in NPOs as a whole are low, market wages are thought to be closer to NPO wages in areas where the market wage is low, making it considered as one possible option to work at NPOs. It is conceivable that Nonprofit corporations can also acquire regular staff more easily in those areas. When NPOs are in a cooperative relationship with local authorities (e.g. via subsidies or commissioning of projects), there is a tendency that more paid staff – not volunteers –

work at NPOs.In Chapter 4, we analyze the wage structure. Based on the wage function, it is pointed out that wage levels are little affected by human capital factors, just as in the survey 10 years ago. Moreover, correlation between years of activity and wages is statistically unconfirmed, just as in prior researches. What has been confirmed, meanwhile, is the impact of age and gender on wages. The results show that wages rise with age, and are higher for men. The tendency is remarkable with male, regular staff. This is a discovery not seen in previous analyses of NPO wages, and suggests that NPO wages are gradually approaching those of the general labor market.

- Intention to continue and changes in career

In Chapter 4, we analyze the degree to which wages affect the intention of paid staff to continue their activity. As a result, it became clear that while the absolute amount of wage does not affect the intention to continue, relative wage factors such as a big difference compared to average wages or a rise in wages lead to continuation of activity.

In Chapter 5, we analyze the relationship between the motives for participation and the intention to continue the activity for younger and middle age groups. On “empathy with philosophy and the purpose of the activity” related to consumption motives, the theoretical model assumes that the intention to continue will be stronger when this motivation is stronger. While the results are in line with the hypothesis, this tendency is seen more strongly in younger and middle age groups than in older age groups. Also, on the investment motive of “acquiring knowledge, technology and experience”, considering that human capital obtained by working for an NPO would be utilized elsewhere in future, the theoretical model assumed that the intention to continue would be weaker as this motive grew stronger. The result was that the intention to continue grows weaker in young and middle age groups, thus concurring with the model assumption. The interesting thing, however, is that the intention to continue is stronger with this motive in older age groups, suggesting that those in older age groups are hoping for a new experience distinct from their career to date.

In Chapter 6, we analyze the age of first participation and the level of involvement in activity from the perspective of second career development by older persons. As a result, it became clear that the lower age of first participation has the effect of increasing the operation and management of the “organization as a whole” and the length of involvement; by reducing the age of first participation from 60 to 55, the probability of involvement in NPO activity at age 65 is doubled.

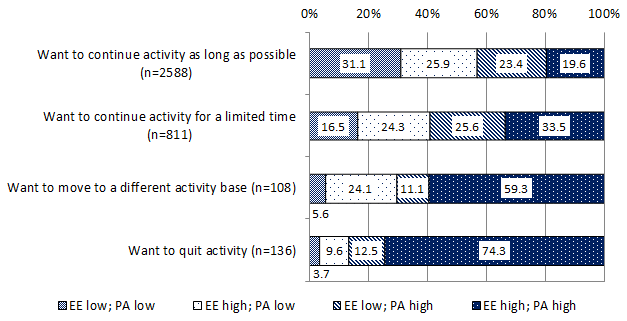

In Chapter 7, we analyze factors behind the psychological state known as “burnout” in NPO activity. As the word “burnout” implies, this is a state in which a person loses the desire to continue working and tends to take time off work or quit altogether. Two indicators are used to measure this state, namely “emotional exhaustion” and “diminished personal accomplishment”. “Emotional exhaustion”, briefly, is a state of being “emotionally drained”, while “diminished personal accomplishment” is a state in which a person loses the motivation gained through work. In the case of long working hours, for example, “emotional exhaustion” rises but “personal accomplishment” does not diminish. On the other hand, in the group that wants to “quit activity”, it became clear that not only “emotional exhaustion” but also “diminished personal accomplishment” rises significantly (Figure 2). That is, job quitting is a final action when a person reaches a state of exhaustion without any sense of achievement, or to put it another way, a person will continue an activity if full of a sense of achievement even though completely exhausted, or conversely, if not so exhausted though with no sense of achievement.

Figure 2. Four types of burnout for each intention to continue activity

―by the level of emotional exhaustion(EE)and personal achievement(PA)―

Note) EE is short for “emotional exhaustion”, while PA for “diminished personal accomplishment”. Each was divided into a high group and a low group to make four possible types, based on the median value of the respective scores.

- The Great East Japan Earthquake and support activity by NPOs

In Chapter 8, we discuss whether changes in working styles and awareness of NPO activists are only temporary ones triggered by the earthquake disaster, or whether they have continuity that could be seen as “structural change”. The conclusion is that a heightened awareness as “workers” is palpable among those who started NPO activity in recent years or who were active in disaster-affected areas. However, there is a question as to whether continuation of activity by NPOs has sufficient sustainability to be called “structural change”, and activists’ intention to continue is more strongly determined by awareness factors than by organizational factors. We therefore conclude that “activities supported by sentiment alone are weak and lack sustainability”.

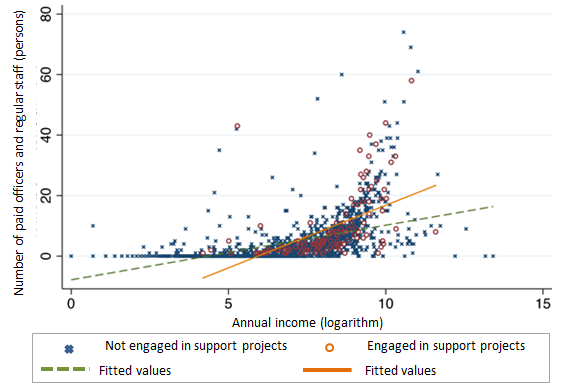

In Chapter 9, we focus on the relationship between the financial situation and employment in Nonprofit corporations that engaged in support activities after the Great East Japan Earthquake. In terms of the financial circumstances of NPOs that were active in the disaster areas, annual revenues expanded for three years after the disaster in most organizations, and the numbers employed also increased in comparison to the national level. In particular, NPOs that were launched after the disaster sourced most of their funding from external capital in the form of grants and subsidies. NPOs implementing reconstruction support projects also tend to appoint more paid officers and regular staff as their annual revenues increase (Figure 3). However, we point out that, while there has been a massive short-term flow of capital for reconstruction projects in the process of disaster reconstruction to date, this will decrease as we can see prospects for the goal of restoration. Given that reconstruction after the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake was by no means finished in the short term, we advocate the need for sustained support.

Figure 3. Numbers of paid officers and regular staff in terms of annual income

In Chapter 10, we analyze the impact of Great East Japan Earthquake support activity on NPOs. As a result, we find that NPOs that undertook support activity (including fundraising) in disaster areas were close to those disaster areas, underlining the importance of “home advantage”. Therefore, we need to explore systems of cooperation at normal times on the assumption of support at neighborhood level. Meanwhile, an NPO that has a strong cooperative relationship with other NPOs tends to undertake greater support activities. Another confirmed tendency is that numbers of regular staff and volunteers in NPOs undertaking support activity not only increase but also decrease in some cases, with human resources tending to become more fluid as a result of support activity. This could be because the situation is still unstable, even if employment increases in the short term due to the inflow of external capital.

In Chapter 11, we discuss the nature of volunteers in the event of a disaster. We need to think how many volunteers can be gathered from all over the country in the disaster reconstruction phase, and how they can be utilized. Japan has no law on protecting or compensating volunteer activities. Volunteers are encouraged to take out insurance when participating in activities, but about half of those active in disaster areas do so without any insurance. In this survey, it became clear that more than 80% of respondents have a positive perception of the government or authorities recruiting and dispatching volunteers and expanding the system of compensation for volunteers. In this chapter, we introduce compensation systems and recruitment methods for volunteer activity in Germany, France and the USA, and discuss the need to develop them in Japan.

Policy Contribution

Measures related to non-profit organizations (NPOs)

Measures related to elderly employment

Great East Japan Earthquake reconstruction support measures

Contents (available only in Japanese)

- JILPT Research Report No.183 / Whole text (PDF:7.8MB)

If it takes too long to download the whole text, please access each file separately.

- Cover – Preface – Authors – Contents (PDF:866KB)

- Chapter 1: Directions for research on NPO employment –– Background to this research and issues for analysis (PDF:752KB)

- Chapter 2: Labor market of Nonprofit corporations: Estimated scale and structure (PDF:2.5MB)

- Chapter 3: Factors and changes in NPO employment of paid staff –– From a comparison between 2004 and 2014 survey data(PDF:2.1MB)

- Chapter 4: The wage structure of Nonprofit corporation staff and how it affects their satisfaction levels and desire to continue activity (PDF:1.7MB)

- Chapter 5: NPOs as a career –– Differences and time-related change in determinants of the intention to continue based on age (PDF:1.3MB)

- Chapter 6: Age of first participation in NPO by older persons and their level of involvement in activities (PDF:1.3MB)

- Chapter 7: NPO employment and burnout (PDF:1.0MB)

- Chapter 8: Will there be a “structural change” in NPO working styles? –– Impact of disasters and time-related change (PDF:1.4MB)

- Chapter 9: Impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the relationship between “finances and employment” of Nonprofit corporations -- Analysis using JILPT survey data and financial data of Nonprofit corporations (PDF:1.1MB)

- Chapter 10: Reconstruction support activity by NPOs –– Impact on participation factors and employment (PDF:781KB)

- Chapter 11: The nature of volunteers and compensation during disasters (PDF:1.5MB)

- Appendices (PDF:1.9MB)

Research Category

Project Research: “Research on Strategic Labor/Employment Policies for Non-regular Workers”

Subtheme: “Survey research on diverse ways of working in both regular and non-regular employment”

Research Period

FY2013 – FY2015

Author

- Akiko ONO

- Senior Researcher, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

- Naoto YAMAUCHI

- Professor, Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University

- Xinxin MA

- Associate Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University

- Tomohiko MORIYAMA

- Lecturer, Department of Economics, Shimonoseki City University

- Shinya KAJITANI

- Associate Professor, School of Economics, Meisei University

- Seiji KOMATA

- Research Assistant, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

- Junko URASAKA

- Professor, Faculty of Social Studies, Doshisha University

- Yu ISHIDA

- Associate Professor, National Institute of Technology, Akashi College

- Yasuhiko KOTAGIRI

- Associate Professor, Graduate School of Integrated Arts and Sciences, Tokushima University

Catergory

Employment / Unemployment, Working conditions / Work environment, Diversified working styles, Workers' life / Workers' awareness

Related Research Results

- JILPT Research Report No.12 "Diversifying Working Styles and Social-Labor Policy" (PDF:64KB)

- JILPT Research Report No.60 "Salaried Staffs and Volunteers at NPOs: Their Working Styles and Attitudes" (PDF:75.5KB)

- JILPT Research Report No.82 "Path to Development of NPO Employment – Seen from Human Resources, Financial and Legal Perspectives – "(PDF:86.1KB)

- JILPT Research Report No.142 "A Study on Elderly People´s Social Contribution Activities -- Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis --" (PDF:236KB)

- Research Series No.139 "Survey on activities and working styles of Nonprofit corporations (group survey, individual survey) –– With partial focus on Great East Japan Earthquake reconstruction support activity” (2015)

JILPT Research Report at a Glance

| To view PDF files, you will need Adobe Acrobat Reader Software installed on your computer.The Adobe Acrobat Reader can be downloaded from this banner. |