JILPT Research Report No.230

Non-regular workers after the “polarization” of employment: Based on analyses of official statistics and survey data

May 30, 2024

Summary

Research Objective

The “polarization” of working conditions and working styles between regular employment (regular employees) and non-regular employment (non-regular employees/workers) has long been an issue. This research report updates the findings on the actual situation of non-regular employment, taking into account that a certain number of years have passed since the recognition of such issues was established and that major environmental changes have occurred, such as the introduction of legal policies aimed at protecting them and the progression of labor shortages. The report summarizes how the situation has changed mainly in the 2010s when major legal reforms concentrated and baby-boomers retired from the labor market.

Research Method

Time series tabulation of official statistics and secondary analyses of survey data

Key Findings

■ Time series tabulations of official statistics (Part 1)

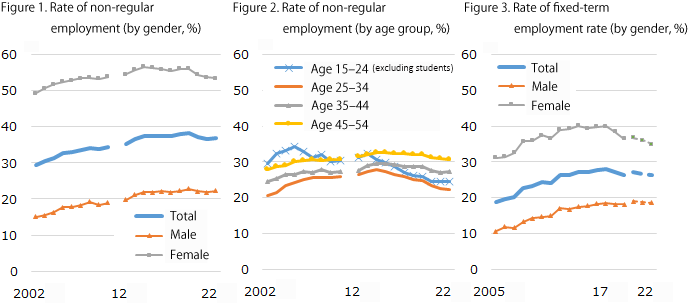

- Chapter 1 indicates that the rate of non-regular workers among all employees excluding executives (non-regular employment rate) has reached a plateau and is trending downward for women and those at working-age under 54 (particularly young generation) (Figures 1 and 2). The rate of fixed-term contract workers in companies with 10 or more employees (fixed-term employment rate) peaked in 2017 and has also been declining (Figure 3).

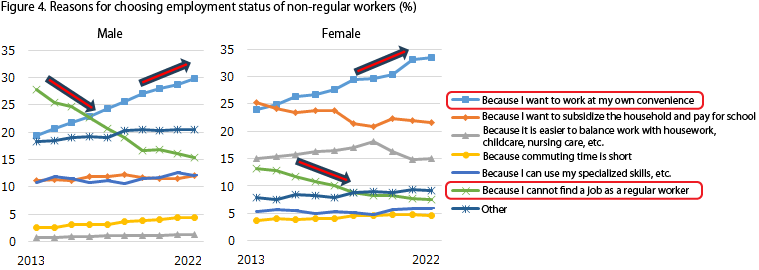

- Chapter 2 looks at the reasons for non-regular workers' choice of employment status. The percentage of “because I cannot find a job as a regular worker” has declined, while that of “because I want to work at my own convenience” has increased (Figure 4). Looking at the reasons for the use of non-regular employees from business establishments’ side, the percentage of “to save wage cost” has declined from 2010 to 2019, while that of “because we cannot secure regular employees” has increased.

Sources: Figures 1 and 2 are based on MIC, Labor Force Survey (Detailed Tabulation) (no data available for 2011), and Figure 3 on MHLW, Basic Survey on Wage Structure (data for 2019 and before and that for 2020 and after are aggregated on different subjects).

Sources: Based on MIC, Labor Force Survey (Detailed Tabulation).

■ Secondary analyses of survey data (Part 2)

- Chapter 3 indicates that the involuntary non-regular employment rate––the rate of those who choose the non-regular job for the reasons such as they could not find a company where they could work as a regular employee––declined from 2010 to 2019. This trend was particularly pronounced among younger workers. The fact that the involuntary non-regular employment rate declined in all segments of the labor market, including segments by education, occupation, industry, and company size, suggests that the hurdles to becoming a regular employee are decreasing overall. This suggests the possibility that those who has remained as involuntary non-regular workers may be people with disadvantages in finding or changing jobs as a regular employee. [Source: MHLW, “General Survey on Diversified Types of Employment.”]

- In Chapter 4, we estimated the wage gap between regular and non-regular workers using a wage function by gender (control variables are years of education, years of experience, years of experience squared, occupation, company size, and industry). The gap remains but is narrowed by 2 to 4 percentage points between 2010 and 2019. [Source: MHLW, “General Survey on Diversified Types of Employment.”]

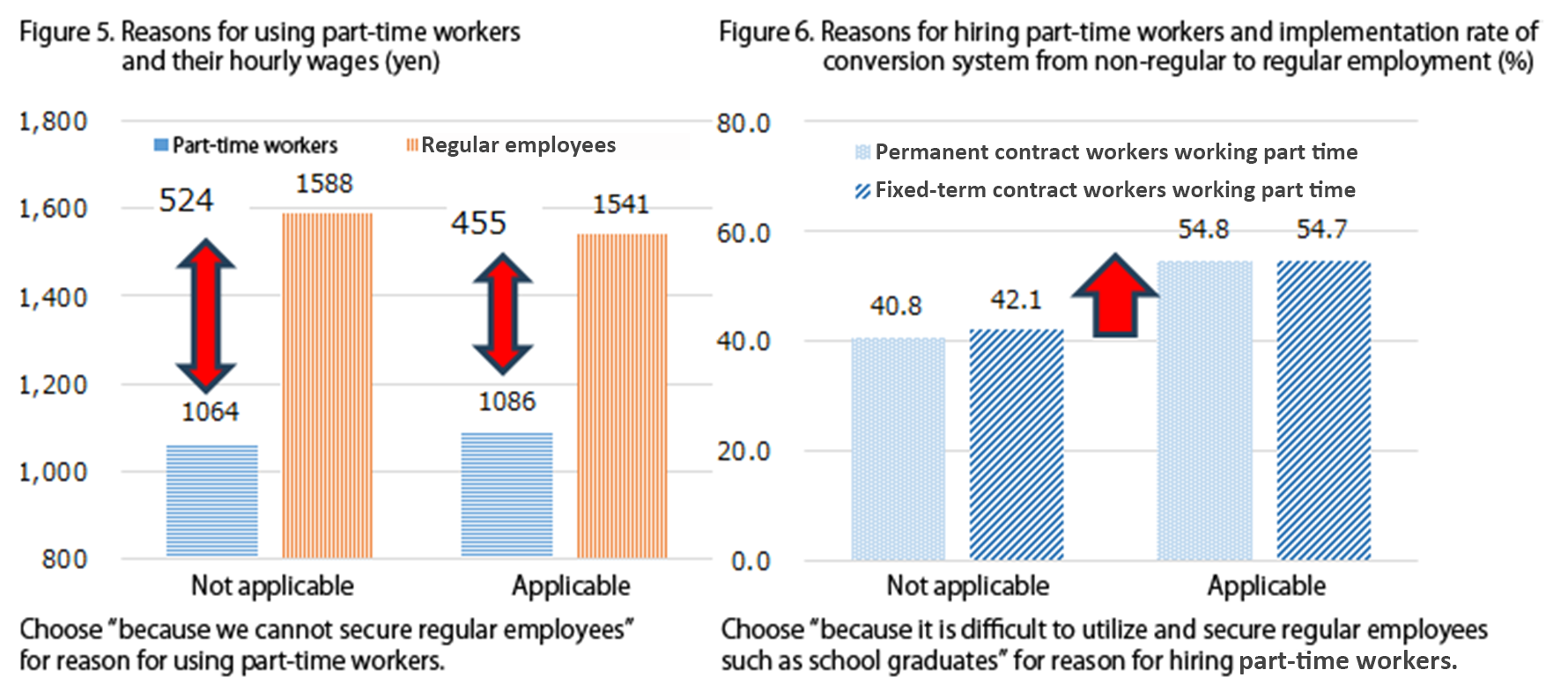

- Chapters 5 and 6 analyzed the characteristics of establishments and companies that use or hire non-regular workers for the reasons such as “because we cannot secure regular employees” or “because it is difficult to utilize and secure regular employees such as school graduates.” At these establishments and companies, wage levels of regular employees are low, but the wage gap between regular employees and non-regular workers is small (Figure 5). Also, such companies seem to be actively responding to the “equal pay for equal work” policy and to have high rates of implementing education and training as well as introducing systems to convert non-regular employees to regular employees (Figure 6).

Regarding the conversion, the percentage of non-regular workers who wish to be converted to regular employees is not necessarily high at these companies that use or hire non-regular workers for reluctant reasons. However, the percentage could be high where the conversion system has been introduced, and, moreover, where they can choose through conversion a “limited regular employee,” such as a regular employee whose working hours are shorter than other regular employees. [Sources: MHLW, “General Survey on Diversified Types of Employment” and “General Survey on Part-Time and Fixed-term Workers.”]

Sources: Figure 5 is based on Figure 6-5-10, and Figure 6 on Figure 5-3-9 in the report (JILPT 2023).

Click to enlarge (Figure 5, 6)

- In Chapter 7, we analyzed the actual conditions and attitudes of those who changed their jobs after the implementation of the so-called “fixed-term to permanent conversion rule” of the Labor Contracts Act. Regarding the difference in treatment with regular employees doing the same job, the dissatisfaction of those who became limited regular employees through the conversion is not necessarily strong. However, regarding the possibility of promotion, the dissatisfaction of such employees is stronger than that in other employment categories. Compared to those who have originally been non-regular employees, those who are non-regular employees even after a conversion are more likely to wish to be converted to regular employees and more dissatisfied with the difference in treatment with regular employees doing the same job. [Source: JILPT “Survey on Diversified Labor Contracts.”]

- In Chapter 8, we analyzed what the dispatched workers (temporary agency workers) hope for their future work style. They tend to wish to continue working as dispatched workers when the dispatching company (temporary agency) provides information on a “system for promoting dispatched workers with fixed-term contract to those with permanent contract,” and when a career consulting service is available. Also, the dispatched workers whose weekly hours worked is short tends to be interested in continuing their dispatch work. The group of short-time dispatched workers who wish to continue their dispatch work are often working under a peculiar work management. [Source: MHLW, “General Survey on Dispatched Workers.”]

Policy Implications

The percentage of non-regular workers has reached its peak and has already begun to decline among women and younger workers. That of fixed-term employment has also begun to decline steadily after peaking in 2017. Companies’ use of non-regular employment to reduce the labor cost (in their wages) has receded, and the wage gap between regular and non-regular workers has narrowed. Among non-regular workers, there has been a decline in the rate of those who choose non-regular jobs involuntarily, and a rise in the responses (in multiple answer options) of those who choose them actively. These facts indicate that the problem of “polarization” between regular and non-regular workers has narrowed to a certain degree.

However, the problem will not be solved overnight. If one asks whether the “polarization” has been resolved or is continuing as a labor policy issue, one should say that it is continuing. In addition, what is more important is to recognize that the nature of the “polarization” is changing.

Through the review of previous studies (in Introduction of the report), we have confirmed that research on non-regular employment and labor under “polarization” has broadly discussed (1) the gap in working conditions between regular and non-regular workers, (2) the reality of involuntary non-regular workers, (3) the conversion of non-regular workers to regular workers, and (4) the nature of the intermediate category between regular and non-regular workers. Drawing on these issues, the following is a description of the changing nature of the “polarization” problem and the policy implications of this change.

- Regarding the disparity in working conditions, although a slight reduction in the wage penalty for non-regular workers has been confirmed, the disparity in wages and employment stability remains large. In addition to closely monitoring the enforcement of the “equal pay for equal work,” the Labor Standards Inspection Offices are required to ensure compliance with the law, taking the recent labor shortage as an opportunity. It is also necessary to continue to examine the factors behind the decline in employment of non-regular workers under the COVID-19 pandemic.

- While the percentage of involuntary non-regular workers has been decreasing, it is possible that those who have disadvantages in finding or changing jobs as regular employees remain as involuntary non-regular workers, although their individual circumstances may vary. Therefore, it would be beneficial to shift the focus of support for them from job search, job placement, and promotion to permanent employment within companies, to more basic job training and job search support. On the other hand, the high degree of freedom in time use is once again attracting attention as a positive aspect of non-regular employment and labor. From this, an increase in the number of part-time workers as fixed-term employment declines, as well as the transition of non-regular workers to freelance or gig workers, is foreseen. The enactment of the Freelance Work Law in November 2024 needs to be closely monitored.

- Conversely, companies and establishments want to promote the conversion of non-regular workers to regular employees, but the workers themselves do not necessarily want to do so. It is necessary to raise the wages of regular employees through price shifting, etc., and also to promote the introduction of “limited regular employees” such as regular employees whose working hours are shorter than other regular employees, from a different or new perspective.

- Regarding the intermediate category between regular and non-regular employees, it will be necessary to discuss the issue in light of the full-fledged implementation of the so-called “fixed-term to permanent conversion rule” of the Labor Contracts Act. First, since those who continue to be non-regular workers even after a change to permanent employment are more dissatisfied with their treatment than non-regular workers who were originally employed for an indefinite period, it is necessary to review wages and other treatment so that their motivation and abilities can be fully utilized. In addition, since those who have become limited regular employees as a result of permanent conversion are dissatisfied with their promotions (although their dissatisfaction with their treatment is generally weak), it is necessary to train them from a long-term perspective and improve the fairness of their treatment in a broader sense, including promotions.

Contents

JILPT Research Report No.230, full text (PDF:28.5MB) [in Japanese]

Category

Diversified working styles, Employment/unemployment, Labor laws/working rules

Research Period

Fiscal year 2023

Researchers

- TAKAHASHI Koji

- Senior Researcher, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

- MORIYAMA Tomohiko

- Researcher, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

- OKAMOTO Takeshi

- Assistant Fellow, The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

- FUKUI Yasutaka

- Associate Professor, Nagoya University

- NISHINO Fumiko

- Professor, Hitotsubashi University

Related Research

- Takahashi, Koji. 2024. "Changes and Continuity in Non-regular Employment in Japan: Improved General Situation, Yet Persistent Gender Structure," Japan Labor Issues, vol.8, no.49, pp.8–13. (PDF:789KB)

- Takahashi, Koji. 2023. “Non-Regular Employment Measures in Japan,” Japan Labor Issues, vol.7, no.44, pp.52–60. (PDF:1.2MB)

- Takahashi, Koji. 2017. “Polarization of Working Styles: Measures to Solve the Polarization and New Category of Regular Employees,” Japan Labor Issues, vol.1, no.1, pp.12–19. (PDF:1.4MB)

- JILPT Research Report No.188, Research on the Work and Lives of Non-Regular Workers in Mid-Prime-Age: Focusing on Conversion to Regular Employment (2017).

- JILPT Research Report No.185, Polarization of Working Styles and Regular Employees: Results of Secondary Analysis of JILPT Questionnaire Surveys (2016).

- JILPT Research Report No.180, Research on the Work and Lives of Non-Regular Workers in Mid-Prime Age: With Focus on Career Analysis (2015)

- JILPT Research Report No.164, Research on the Work and Lives of Middle-aged (35-44) Non-Regular Workers: Analysis of Present Situation (2014).

- JILPT Research Report No.161, Transition in Diversification of Employment III: 2003 / 2007 / 2010/ Based on Special Tabulation of the “Survey on Diversification of Employment” of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2013).

- JILPT Research Report No.115, Transition in Diversification of Employment II: 2003-2007––Based on a Special Tabulation of the "Survey on Diversification of Employment" of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2010). (PDF:269KB)

- JILPT Research Report No.68, Transition of Diversification of Employment between 1994 and 2003 (2006). (PDF:305KB)

JILPT Research Report at a Glance

| To view PDF files, you will need Adobe Acrobat Reader Software installed on your computer.The Adobe Acrobat Reader can be downloaded from this banner. |